Olympic Games History: From Ancient to Modern

Olympic Games History : Ancient Era

Olympic Games History, Olympia: A Sacred Sanctuary of Ancient Greece and the Inaugural Site of the Olympic Games

Olympic Games. Established nearly 2,800 years ago, these early games were a spectacle exclusively for male athletes who competed in the nude, a tradition that emphasized the athletic form and celebrated the human physique. The significance of these games was such that even wars were temporarily halted, allowing for a period of peace and celebration dedicated to the festivities. This practice is extraordinarily noteworthy, especially given that the early Olympic Games featured just a single event: a 200-yard sprint known as the stadion race.

Despite the limited number of events, the competition was intense, with athletes dedicating weeks in Olympia to rigorous preparation and training. Participation in the games was restricted solely to free men from across the Greek Empire, creating a unique gathering of the best athletes from various city-states. Given the era’s limited communication methods, the dissemination of the results took considerably longer, spreading slowly across the vast reaches of the Greek world. The dedication to preparation, the exclusivity of participation, and the slow spread of information all underscore the remarkable nature of these early Olympic Games, reflecting the enduring legacy and historical significance of Olympia.

Although they originated in ancient times, by the end of the 6th century BCE, four major Greek sporting festivals, often referred to as the “classical games,” had achieved significant importance. These included the famed Olympic Games held at Olympia, the Pythian Games at Delphi, the Nemean Games at Nemea, and the Isthmian Games near Corinth. These events became central to Greek culture and attracted participants and spectators from all over the Greek world.

As these festivals gained popularity, the concept of athletic competitions spread to numerous other cities. Eventually, similar festivals were hosted in nearly 150 locations, including notable cities such as Rome, Naples, Odessus, Antioch, and Alexandria. This widespread adoption demonstrates the extensive influence of Greek athletic traditions.

The proliferation of these games indicates the high value placed on athletic achievement and the cultural importance of physical competitions in ancient societies. Each new venue that embraced these games added its unique characteristics to the events, enriching the overall tradition of athletic contests. This expansion underscores the universal appeal of sports and their ability to bring together diverse communities. The enduring legacy of these classical games highlights the significant role they played in shaping athletic practices and their lasting impact on future generations. The continued celebration of these festivals across such a vast area reflects the shared human fascination with physical excellence and competitive spirit.

The interval between the Olympic Games, held every four years in Olympia, Greece, was so significant that historians used it as a time measurement, the Olympiad. These games, honoring Zeus, were the most prestigious of Greek festivals, starting with a sprint race won by Coroebus in 776 BCE. Despite myths attributing the games to Heracles, historical evidence points to a later origin. The games concluded on September 19, following an August 6 start.

The Olympic Games, a quadrennial athletic and religious festival held in Olympia, Greece, were a pivotal event in the ancient world. Originating around 776 BCE, they evolved from a simple footrace into a complex series of contests that showcased the pinnacle of Greek athleticism and cultural values.

Initially a celebration honoring Zeus, the Games transcended their religious roots to become a panhellenic gathering, uniting often-rival city-states in a shared experience. Over centuries, the athletic program expanded to encompass wrestling, boxing, chariot racing, and the brutal pancratium, a no-holds-barred combat sport. These events tested not only physical prowess but also courage, endurance, and mental fortitude.

A distinctive feature of the ancient Olympics was the nudity of the athletes. This practice, while perplexing to modern sensibilities, was deeply ingrained in Greek culture. Theories abound about its significance, ranging from religious ritual to social custom, but the precise reasons remain elusive.

Participation in the Games was restricted to freeborn Greek males, yet athletes came from across the Hellenic world, including colonies in Italy, Asia Minor, and Africa. Many were professionals who trained rigorously for years, driven by the allure of victory and the substantial rewards often bestowed upon champions by their home cities in Olympic games history. While the official prize was an olive wreath, the true recompense was the unparalleled fame and prestige associated with Olympic glory.

Beyond the athletic contests, the Olympics served as a powerful platform for cultural exchange, political maneuvering, and the reinforcement of Greek identity. In Olympic games history, the Games embodied the Hellenic ideals of beauty, harmony, and competition, shaping the values and aspirations of a civilization. As such, they remain a potent symbol of the enduring spirit of human achievement.

From the Olympian sanctuary, a quadrennial spectacle ignited. The Olympic Games, a crucible of Greek prowess, emerged from a modest footrace around 776 BCE into a panhellenic extravaganza. Not merely athletic contests, they were a sacred ritual, a cauldron of competition where gods and mortals intertwined.

Zeus, the sky-father, cast his shadow over Olympia, a hallowed ground where athletes, stripped bare of artifice, clashed in a dance of strength and spirit. Wrestling, boxing, the chariot’s thunder, and the brutal pancratium expanded the Olympic repertoire, demanding not just physical dominance but a fusion of courage, endurance, and tactical acumen.

Naked bodies, glistening in the Aegean sun, became a canvas for myth and philosophy. Were they vessels of religious purity, relics of primal instincts, or simply a societal norm? The enigma persists, a testament to the chasm between ancient and modern sensibilities.

An exclusive domain for freeborn Greek males, the Olympics beckoned athletes from the heartland and the empire’s farthest reaches. These were not mere competitors; they were icons, sculpted by relentless training and fueled by the promise of immortal fame. Victory was more than a laurel crown; it was a passport to a hero’s welcome, a life transformed by adulation and often tangible rewards.

Beyond the arena, the Olympics were a geopolitical stage, a microcosm of Greek aspirations. City-states clashed, not with swords, but in the arena of athletic supremacy. The Games were a cultural barometer, reflecting the evolution of Greek society, art, and philosophy.

In the crucible of Olympia, the human spirit was forged. It was a stage where ideals of beauty, discipline, and competition were celebrated, where the boundaries of human potential were relentlessly pushed. The Olympic legacy, etched in the annals of history, continues to inspire, challenge, and unite.

When Rome’s shadow engulfed Greece in the 2nd century BCE, the Olympic flame began to flicker. A century later, the once-bright beacon was nearly extinguished. The Romans, a culture forged in conquest, not competition, viewed the naked contests of the Greeks with disdain. Their spectacles were of a different breed: gladiatorial arenas and chariot circuses, where dominance, not athleticism, was paramount.

Eclipse of the Olympic Ideal

Yet, the Romans were astute politicians. They recognized the Olympic Games as a potent symbol, a tool to manipulate and control. Augustus Caesar, the empire’s architect, transformed the Games into Roman propaganda, staging spectacles for Greek athletes in a grand arena near the Circus Maximus. Nero, a narcissistic emperor, further tarnished the Olympic ideal with his farcical chariot victory.

The chasm between Greek and Roman approaches to athleticism was profound. For the Greeks, the Games were a sacred contest, a celebration of human potential. For the Romans, they were mere entertainment, a bread and circuses diversion. In the end, the Olympic flame was snuffed out by Theodosius I, a Christian emperor who saw in the Games the remnants of a pagan world he sought to eradicate.

Thus, in Olympic games history, the Olympic ideal, born in the heart of Greece, perished under the weight of empire and the rise of a new faith.

Olympic Games History: The modern Olympic

From Ruins to Renaissance: The Olympic Revival

The resurgence of the Olympic Games in Olympic games history at the late 19th century was not a spontaneous combustion but a culmination of decades of aspiration and effort. While Pierre de Coubertin is often hailed as the sole architect of the modern Olympics, his role was more that of a catalyst than a creator.

The foundation was laid by figures such as Dr. William Penny Brookes, a British educator and sports enthusiast. Inspired by the grandeur of the ancient Games, Brookes devoted much of his life to reviving the Olympic spirit. He organized a series of “Olympic” competitions in England, laying the groundwork for what would later become a global phenomenon. Brookes’ vision, however, was confined to the British Isles, lacking the international scope necessary to truly resurrect the ancient ideal.

Enter Pierre de Coubertin. A young French aristocrat with a keen interest in education and physical culture, Coubertin discovered Brookes’ work and became captivated by the idea of reviving the Olympic Games on a global scale. Possessing a unique blend of vision, charisma, and organizational skills, Coubertin transformed the concept from a local endeavor into an international movement.

In 1892, at a conference of sports leaders in Paris, Coubertin boldly proposed the re-establishment of the Olympic Games as a quadrennial international event. His speech was met with a mixture of skepticism and indifference. Yet, Coubertin was undeterred. With unwavering determination, he rallied support, emphasizing the potential of the Olympics to foster international understanding and peace.

The turning point came in 1894 when Coubertin convened another international sports congress in Paris. With careful diplomacy and persuasive oratory, he convinced delegates from various nations to embrace his vision. The International Olympic Committee (IOC) was formed, and Athens, the birthplace of the original Games, was chosen to host the first modern Olympics in 1896.

The path to the first modern Olympics was fraught with challenges. Financial constraints, logistical hurdles, and skepticism about the viability of such a grand undertaking threatened to derail the project. However, Coubertin and his collaborators persevered, overcoming obstacles through sheer force of will and a deep belief in the transformative power of the Olympic ideal.

The inaugural Athens Games were a modest affair by today’s standards, but they marked the beginning of a new era. The Olympic flame had been rekindled, and its light would grow steadily brighter in the decades to come. While Coubertin’s role in the revival is undeniable, it is essential to recognize the contributions of those who came before him and the collective effort that brought the Olympic dream to fruition.

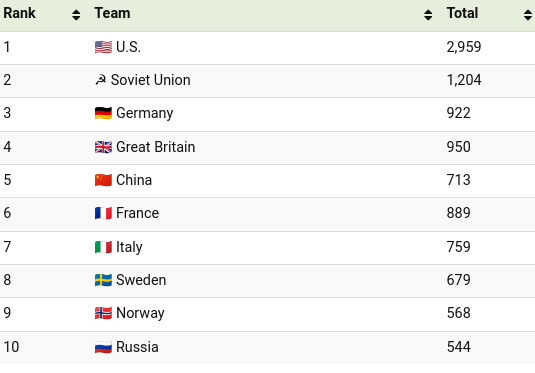

Top 10 Countries by Olympic Medal Count as per 2024:

References:

Abrahams, H. Maurice and Young, . David C.. “Olympic Games.” Encyclopedia Britannica, July 22, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/sports/Olympic-Games.

https://www.visualcapitalist.com/which-countries-have-the-most-olympic-medals-of-all-time/

Responses